The area that is now

was colonized by

English settlers

The English people are an ethnic group and nation native to England, who speak the English language, a West Germanic language, and share a common history and culture. The English identity is of Anglo-Saxon origin, when they were known in ...

in the early 17th century and became the

in the 18th century. Before that, it was inhabited by a variety of Indian tribes. The

Pilgrim Fathers

The Pilgrims, also known as the Pilgrim Fathers, were the English settlers who came to North America on the ''Mayflower'' and established the Plymouth Colony in what is today Plymouth, Massachusetts, named after the final departure port of Plymo ...

who sailed on the ''

Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, r ...

'' established the first permanent settlement in 1620 at

Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the British America, first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the pa ...

which set precedents but never grew large. A large-scale

Puritan migration

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

began in 1630 with the establishment of the

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

, and that spawned the settlement of other

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

colonies.

As the Colony grew, businessmen established wide-ranging trade, sending ships to the

West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

and Europe. Britain began to increase taxes on the New England colonies, and tensions grew with implementation of the

Navigation Acts

The Navigation Acts, or more broadly the Acts of Trade and Navigation, were a long series of English laws that developed, promoted, and regulated English ships, shipping, trade, and commerce between other countries and with its own colonies. The ...

. These political and trade issues led to the revocation of the Massachusetts charter in 1684. The king established the

Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was an administrative union of English colonies covering New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies (except for Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvania). Its political structure represe ...

in 1686 to govern all of New England, and to centralize royal control and weaken local government. Sir

Edmund Andros

Sir Edmund Andros (6 December 1637 – 24 February 1714) was an English colonial administrator in British America. He was the governor of the Dominion of New England during most of its three-year existence. At other times, Andros served ...

's intensely unpopular rule came to a sudden end in 1689 with

an uprising sparked by the

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

in England. The new king

William III William III or William the Third may refer to:

Kings

* William III of Sicily (c. 1186–c. 1198)

* William III of England and Ireland or William III of Orange or William II of Scotland (1650–1702)

* William III of the Netherlands and Luxembourg ...

established the

Province of Massachusetts Bay

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a colony in British America which became one of the Thirteen Colonies, thirteen original states of the United States. It was chartered on October 7, 1691, by William III of England, William III and Mary II ...

in 1691 to govern a territory roughly equivalent to the modern states of

and

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

. Its governors were appointed by the crown, unlike the predecessor colonies that had elected their own governors. This increased friction between the colonists and the crown, which reached its height in the days leading up to the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

in the 1760s and 1770s over the question of who could levy taxes. The

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

began in Massachusetts in 1775 when London tried to shut down American self-government.

The commonwealth formally adopted the

state constitution in 1780, electing

John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of the ...

as its first governor. In the 19th century,

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

became America's center of manufacturing with the development of precision manufacturing and weaponry in

Springfield

Springfield may refer to:

* Springfield (toponym), the place name in general

Places and locations Australia

* Springfield, New South Wales (Central Coast)

* Springfield, New South Wales (Snowy Monaro Regional Council)

* Springfield, Queenslan ...

and

Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since the ...

, and large-scale textile mill complexes in

Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Englan ...

,

Haverhill,

Lowell, and other communities throughout New England using their rivers for power. New England also was an intellectual center and center of abolitionism. The

Springfield Armory

The Springfield Armory, more formally known as the United States Armory and Arsenal at Springfield located in the city of Springfield, Massachusetts, was the primary center for the manufacture of United States military firearms from 1777 until ...

made most of the weaponry for the Union in the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. After the war, immigrants from

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, The

Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

and

Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

flooded into

, continuing to expand its industrial base until the 1950s when textiles and other industries started to fade away, leaving a "rust belt" of empty mills and factories.

Labor unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

were important after the 1860s, as was big-city politics. The state's strength as a center of education contributed to the development of an economy based on information technology and biotechnology in the later years of the 20th century, leading to the "

Massachusetts Miracle

The Massachusetts Miracle was a period of economic growth in Massachusetts during most of the 1980s. Before then, the state had been hit hard by deindustrialization and resulting unemployment. During the Miracle, the unemployment rate fell from ...

" of the late 1980s.

Before European settlement

Massachusetts was originally inhabited by tribes of the

Algonquian language family

The Algonquian languages ( or ; also Algonkian) are a subfamily of indigenous American languages that include most languages in the Algic language family. The name of the Algonquian language family is distinguished from the orthographically simi ...

such as the

Wampanoag

The Wampanoag , also rendered Wôpanâak, are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands based in southeastern Massachusetts and historically parts of eastern Rhode Island,Salwen, "Indians of Southern New England and Long Island," p. 17 ...

,

Narragansetts

The Narragansett people are an Algonquian American Indian tribe from Rhode Island. Today, Narragansett people are enrolled in the federally recognized Narragansett Indian Tribe. They gained federal recognition in 1983.

The tribe was nearly lan ...

,

Nipmuc

The Nipmuc or Nipmuck people are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who historically spoke an Eastern Algonquian language. Their historic territory Nippenet, "the freshwater pond place," is in central Massachusetts and nearby part ...

s,

Pocomtuc

The Pocumtuc (also Pocomtuck or Deerfield Indians) were a Native American tribe historically inhabiting western areas of Massachusetts.

Settlements

Their territory was concentrated around the confluence of the Deerfield and Connecticut Rivers ...

s,

Mahican

The Mohican ( or , alternate spelling: Mahican) are an Eastern Algonquian Native American tribe that historically spoke an Algonquian language. As part of the Eastern Algonquian family of tribes, they are related to the neighboring Lenape, who ...

s, and

Massachusett

The Massachusett were a Native American tribe from the region in and around present-day Greater Boston in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name comes from the Massachusett language term for "At the Great Hill," referring to the Blue Hills ...

s.

[Brown and Tager, pp. 6–7.] The

Vermont

Vermont () is a state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to ...

and

New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

borders and the

Merrimack River

The Merrimack River (or Merrimac River, an occasional earlier spelling) is a river in the northeastern United States. It rises at the confluence of the Pemigewasset and Winnipesaukee rivers in Franklin, New Hampshire, flows southward into Mas ...

valley was the traditional home of the

Pennacook

The Pennacook, also known by the names Penacook and Pennacock, were an Algonquian-speaking Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands who lived in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and southern Maine. They were not a united tribe but a netwo ...

tribe.

Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mont ...

,

Nantucket

Nantucket () is an island about south from Cape Cod. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and County of Nantucket, a combined county/town government that is part of the U.S. state of Massachuse ...

,

Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard, often simply called the Vineyard, is an island in the Northeastern United States, located south of Cape Cod in Dukes County, Massachusetts, known for being a popular, affluent summer colony. Martha's Vineyard includes the s ...

, and southeast Massachusetts were the home of the Wampanoags who established a close bond with the

Pilgrim Fathers

The Pilgrims, also known as the Pilgrim Fathers, were the English settlers who came to North America on the ''Mayflower'' and established the Plymouth Colony in what is today Plymouth, Massachusetts, named after the final departure port of Plymo ...

. The extreme end of the Cape was inhabited by the closely related

Nauset

The Nauset people, sometimes referred to as the Cape Cod Indians, were a Native American tribe who lived in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. They lived east of Bass River and lands occupied by their closely-related neighbors, the Wampanoag.

Although the ...

tribe. Much of the central portion and the

Connecticut River

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Island ...

valley was home to the loosely organized Nipmucs. The

Berkshires

The Berkshires () are a highland geologic region located in the western parts of Massachusetts and northwest Connecticut. The term "Berkshires" is normally used by locals in reference to the portion of the Vermont-based Green Mountains that ex ...

were the home of both the Pocomtuc and the Mahican tribes. Narragansetts from

Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

and Mahicans from

Connecticut Colony

The ''Connecticut Colony'' or ''Colony of Connecticut'', originally known as the Connecticut River Colony or simply the River Colony, was an English colony in New England which later became Connecticut. It was organized on March 3, 1636 as a settl ...

were also present.

These tribes were generally dependent on hunting and fishing for most of their food supply.

[ Villages consisted of lodges called ]wigwams

A wigwam, wickiup, wetu (Wampanoag), or wiigiwaam (Ojibwe, in syllabics: ) is a semi-permanent domed dwelling formerly used by certain Native American tribes and First Nations people and still used for ceremonial events. The term ''wickiup'' ...

as well as long houses,[ and tribes were led by male or female elders known as ]sachem

Sachems and sagamores are paramount chiefs among the Algonquians or other Native American tribes of northeastern North America, including the Iroquois. The two words are anglicizations of cognate terms (c. 1622) from different Eastern Al ...

s. Europeans began exploring the coast in the 16th century, but they made few attempts at permanent settlement anywhere. Early European explorers of the New England coast included Bartholomew Gosnold

Bartholomew Gosnold (1571 – 22 August 1607) was an English barrister, explorer and privateer who was instrumental in founding the Virginia Company in London and Jamestown in colonial America. He led the first recorded European expedition to ...

who named Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mont ...

in 1602, Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fre ...

who charted the northern coast as far as Cape Cod in 1605 and 1606, John Smith, and Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson ( 1565 – disappeared 23 June 1611) was an English sea explorer and navigator during the early 17th century, best known for his explorations of present-day Canada and parts of the northeastern United States.

In 1607 and 160 ...

. Fishing ships from Europe also worked in the rich waters off the coast, and may have traded with some of the tribes. Large numbers of Indians were decimated by virgin soil epidemics, perhaps including smallpox, measles, influenza, or leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a blood infection caused by the bacteria ''Leptospira''. Signs and symptoms can range from none to mild (headaches, muscle pains, and fevers) to severe ( bleeding in the lungs or meningitis). Weil's disease, the acute, severe ...

.[; Marr, JS and Cathey, JT, "New hypothesis for cause of an epidemic among Native Americans, New England, 1616–1619," ''Emerging Infectious Diseases'', 2010 Feb.] In 1617–1619, a disease killed 90 percent of the Indians in the region.

Pilgrims and Puritans: 1620–1629

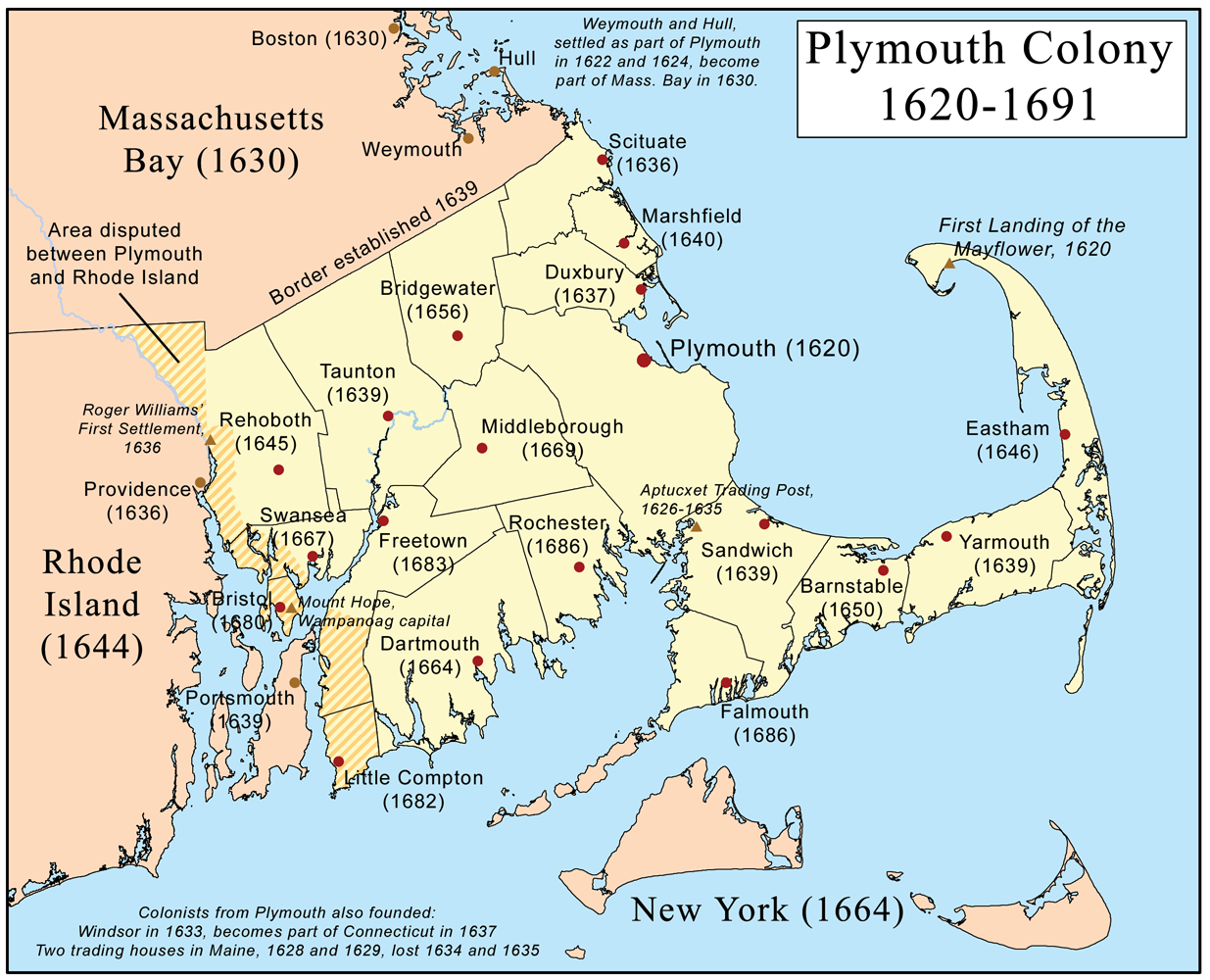

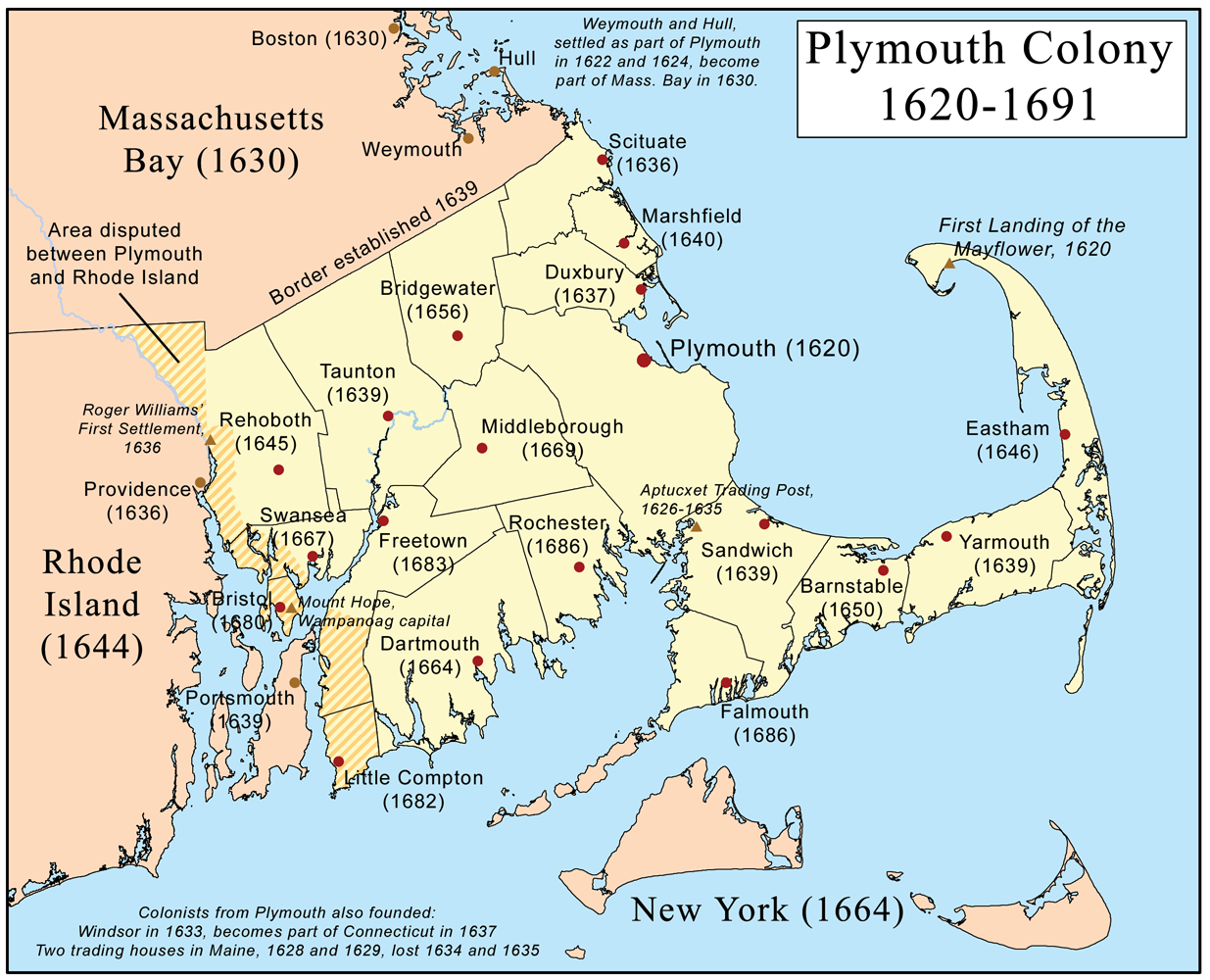

The first settlers in Massachusetts were the Pilgrims who established

The first settlers in Massachusetts were the Pilgrims who established Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the British America, first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the pa ...

in 1620 and developed friendly relations with the Wampanoag people

The Wampanoag , also rendered Wôpanâak, are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands based in southeastern Massachusetts and historically parts of eastern Rhode Island,Salwen, "Indians of Southern New England and Long Island," p. 17 ...

. This was the second permanent English colony in America following Jamestown Colony

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent English settlement

''English Settlement'' is the fifth studio album and first double album by the English rock band XTC, released 12 February 1982 on Virgin Reco ...

. The Pilgrims had migrated from England to Holland to escape religious persecution for rejecting England's official church. They were allowed religious liberty in Holland, but they gradually became concerned that the next generation would lose their distinct English heritage. They approached the Virginia Company and asked to settle "as a distinct body of themselves" in America. In the fall of 1620, they sailed to America on the ''Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, r ...

'', first landing near Provincetown

Provincetown is a New England town located at the extreme tip of Cape Cod in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, in the United States. A small coastal resort town with a year-round population of 3,664 as of the 2020 United States Census, Provincet ...

at the tip of Cape Cod. The area did not lie within their charter, so the Pilgrims created the Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, r ...

Compact before landing, one of America's first documents of self-governance. The first year was extremely difficult, with inadequate supplies and very harsh weather, but Wampanoag sachem Massasoit

Massasoit Sachem () or Ousamequin (c. 15811661)"Native People" (page), "Massasoit (Ousamequin) Sachem" (section),''MayflowerFamilies.com'', web pag was the sachem or leader of the Wampanoag confederacy. ''Massasoit'' means ''Great Sachem''.

Mas ...

and his people assisted them.

In 1621, the Pilgrims celebrated their first Thanksgiving Day together to thank God for the blessings of good harvest and survival. This Thanksgiving came to represent the peace that existed at that time between the Wampanoags and the Pilgrims, although only about half of the Mayflower company survived the first year. The colony grew slowly over the next ten years, and was estimated to have 300 inhabitants by 1630.

A group of fur-trappers and traders established

In 1621, the Pilgrims celebrated their first Thanksgiving Day together to thank God for the blessings of good harvest and survival. This Thanksgiving came to represent the peace that existed at that time between the Wampanoags and the Pilgrims, although only about half of the Mayflower company survived the first year. The colony grew slowly over the next ten years, and was estimated to have 300 inhabitants by 1630.

A group of fur-trappers and traders established Wessagusset Colony

Wessagusset Colony (sometimes called the Weston Colony or Weymouth Colony) was a short-lived English trading colony in New England located in Weymouth, Massachusetts. It was settled in August 1622 by between fifty and sixty colonists who were ill-p ...

near the Plymouth colony in Weymouth in 1622. They abandoned it in 1623, and it was replaced by another small colony led by Robert Gorges

Robert Gorges (1595 – late 1620s) was a captain in the Royal Navy and briefly Governor-General of New England from 1623 to 1624. He was the son of Sir Ferdinando Gorges. After having served in the Venetian wars, Gorges was given a commissio ...

. This settlement also failed, and individuals from these colonies returned to England, joined the Plymouth colonists, or established individual outposts elsewhere on the shores of Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its ...

. In 1624, the Dorchester Company

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as th ...

established a settlement on Cape Ann

Cape Ann is a rocky peninsula in northeastern Massachusetts, United States on the Atlantic Ocean. It is about northeast of Boston and marks the northern limit of Massachusetts Bay. Cape Ann includes the city of Gloucester and the towns of ...

. This colony only survived until 1626, although a few settlers remained.

Massachusetts Bay Colony: 1628–1686

The Pilgrims were followed by

The Pilgrims were followed by Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

s who established the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

at Salem (1629) and Boston (1630). The Puritans strongly dissented from the theology and church polity of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, and they came to Massachusetts for religious freedom. The Bay Colony was founded under a royal charter, unlike Plymouth Colony. The Puritan migration was mainly from East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

and southwestern regions of England, with an estimated 20,000 immigrants between 1628 and 1642. Massachusetts Bay colony quickly eclipsed Plymouth in population and economy, the chief factors being the large influx of population, more suitable harbor facilities for trade, and the growth of a prosperous merchant class.

Religious dissension and expansionism led to the founding of several new colonies shortly after Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay. Dissenters such as Roger Williams

Roger Williams (21 September 1603between 27 January and 15 March 1683) was an English-born New England Puritan minister, theologian, and author who founded Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation ...

and Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (née Marbury; July 1591 – August 1643) was a Puritan spiritual advisor, religious reformer, and an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her ...

were banished due to religious disagreements with Massachusetts Bay authorities. Williams established Providence Plantations

Providence Plantations was the first permanent European American settlement in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. It was established by a group of colonists led by Roger Williams and Dr. John Clarke who left Massachusetts Bay ...

in 1636. Over the next few years, another group, which included Hutchinson, established Newport and Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

; these settlements eventually joined to form the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was one of the original Thirteen Colonies established on the east coast of America, bordering the Atlantic Ocean. It was founded by Roger Williams. It was an English colony from 1636 until ...

. Others left Massachusetts Bay in order to establish other settlements, including Connecticut Colony

The ''Connecticut Colony'' or ''Colony of Connecticut'', originally known as the Connecticut River Colony or simply the River Colony, was an English colony in New England which later became Connecticut. It was organized on March 3, 1636 as a settl ...

on the Connecticut River

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Island ...

and New Haven Colony

The New Haven Colony was a small English colony in North America from 1638 to 1664 primarily in parts of what is now the state of Connecticut, but also with outposts in modern-day New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware.

The history o ...

on the coast.

In 1636, a group of settlers led by William Pynchon

William Pynchon (October 11, 1590 – October 29, 1662) was an English colonist and fur trader in North America best known as the founder of Springfield, Massachusetts, USA. He was also a colonial treasurer, original patentee of the Massachu ...

founded Springfield, Massachusetts

Springfield is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States, and the seat of Hampden County. Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, the ...

(originally named Agawam), after scouting for the region's most advantageous location for trading and farming.Pequot War

The Pequot War was an armed conflict that took place between 1636 and 1638 in New England between the Pequot tribe and an alliance of the colonists from the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Saybrook colonies and their allies from the Narragans ...

. Massachusetts Bay Colony's southern and western borders were thus established in 1640.

King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

(1675–76) was the bloodiest Indian war

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

of the colonial period. In little over a year, Indians attacked nearly half of the region's towns, and they burned to the ground the major settlements at Providence

Providence often refers to:

* Providentia, the divine personification of foresight in ancient Roman religion

* Divine providence, divinely ordained events and outcomes in Christianity

* Providence, Rhode Island, the capital of Rhode Island in the ...

and Springfield

Springfield may refer to:

* Springfield (toponym), the place name in general

Places and locations Australia

* Springfield, New South Wales (Central Coast)

* Springfield, New South Wales (Snowy Monaro Regional Council)

* Springfield, Queenslan ...

. New England's economy was all but ruined, and much of its population was killed. Proportionately, it was one of the bloodiest and costliest wars in the history of North America.Massachusetts legislature

The Massachusetts General Court (formally styled the General Court of Massachusetts) is the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name "General Court" is a hold-over from the earliest days of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, w ...

established a mint to produce the pine tree shilling

The pine tree shilling was a type of coin minted and circulated in the thirteen colonies.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony established a mint in Boston in 1652. John Hull was Treasurer and mintmaster; Hull's partner at the "Hull Mint" was Robert S ...

beginning in 1652. John Hull and his partner Robert Sanderson in charge of the "Hull Mint". In 1645, the General Court ordered rural towns to increase sheep production. Sheep provided meat and especially wool for the local cloth industry, avoiding the expense of imports of British cloth. Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660 and began to scrutinize the governmental oversight in the colonies, and Parliament passed the Navigation Acts

The Navigation Acts, or more broadly the Acts of Trade and Navigation, were a long series of English laws that developed, promoted, and regulated English ships, shipping, trade, and commerce between other countries and with its own colonies. The ...

to regulate trade for England's benefit. Massachusetts and Rhode Island had thriving merchant fleets, and they often ran afoul of the trade regulations. King Charles formally vacated the Massachusetts charter in 1684.

Friction erupted with the Indians in King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

in the 1670s. Puritanism was the established religion in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and dissenters were banished, leading to the establishment of the Rhode Island Colony

The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was one of the original Thirteen Colonies established on the east coast of America, bordering the Atlantic Ocean. It was founded by Roger Williams. It was an English colony from 1636 until 1 ...

.

Dominion of New England: 1686–1692

In 1660, King Charles II was restored to the throne. Colonial matters brought to his attention led him to propose the amalgamation of all of the New England colonies into a single administrative unit. In 1685, he was succeeded by James II, an outspoken Catholic who implemented the proposal. In June 1684, the charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was annulled, but its government continued to rule until James appointed Joseph Dudley

Joseph Dudley (September 23, 1647 – April 2, 1720) was a colonial administrator, a native of Roxbury in Massachusetts Bay Colony, and the son of one of its founders. He had a leading role in the administration of the Dominion of New England ...

to the new post of President of New England in 1686. Dudley established his authority later in New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

and the King's Province (part of current Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

), maintaining this position until Sir Edmund Andros

Sir Edmund Andros (6 December 1637 – 24 February 1714) was an English colonial administrator in British America. He was the governor of the Dominion of New England during most of its three-year existence. At other times, Andros served ...

arrived to become the Royal Governor of the Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was an administrative union of English colonies covering New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies (except for Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvania). Its political structure represe ...

. The rule of Andros was unpopular. He ruled without a representative assembly, vacated land titles, restricted town meetings, enforced the Navigation Acts, and promoted the Church of England, angering virtually every segment of Massachusetts colonial society. Andros dealt a major blow to the colonists by challenging their title to the land; unlike England the great majority of New Englanders were land-owners. Taylor says that because they "regarded secure real estate as fundamental to their liberty, status, and prosperity, the colonists felt horrified by the sweeping and expensive challenge to their land titles."

After James II was overthrown by William III William III or William the Third may refer to:

Kings

* William III of Sicily (c. 1186–c. 1198)

* William III of England and Ireland or William III of Orange or William II of Scotland (1650–1702)

* William III of the Netherlands and Luxembourg ...

and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 166228 December 1694) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland, co-reigning with her husband, William III & II, from 1689 until her death in 1694.

Mary was the eldest daughter of James, Duke of York, and his first wife ...

in late 1688, Boston colonists overthrew Andros and his officials in 1689. Both Massachusetts and Plymouth returned to their previous governments until 1692. During King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand All ...

(1689–1697), the colony launched an unsuccessful expedition against Quebec under Sir William Phips

Sir William Phips (or Phipps; February 2, 1651 – February 18, 1695) was born in Maine in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and was of humble origin, uneducated, and fatherless from a young age but rapidly advanced from shepherd boy, to shipwright, s ...

in 1690, which had been financed by issuing paper bonds set against the gains expected from taking the city. The colony continued to be on the front lines of the war, and experienced widespread French and Indian raids on its northern and western frontiers.

Royal Province of Massachusetts Bay: 1692–1774

In 1691, William and Mary chartered the Province of Massachusetts Bay

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a colony in British America which became one of the Thirteen Colonies, thirteen original states of the United States. It was chartered on October 7, 1691, by William III of England, William III and Mary II ...

, combining the territories of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Maine, Nova Scotia (which then included New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

), and the islands south of Cape Cod. For its first governor they chose Sir William Phips. Phips came to Boston in 1692 to begin his rule, and was immediately thrust into the witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have us ...

hysteria in Salem. He established the court that heard the notorious Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Thirty people were found guilty, 19 of whom w ...

, and oversaw the war effort until he was recalled in 1694.

Economy

The province was the largest and most economically important in

The province was the largest and most economically important in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, and one where many American institutions and traditions were formed. Unlike southern colonies, it was built around small towns rather than scattered farms. The westernmost portion of Massachusetts, the Berkshires, was settled during the three decades following the end of the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

, largely by Scots. Sir Francis Bernard, the Royal Governor, named this new area "Berkshire" after his home county in England. The largest settlement in Berkshire County was Pittsfield, Massachusetts

Pittsfield is the largest city and the county seat of Berkshire County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the principal city of the Pittsfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area which encompasses all of Berkshire County. Pittsfield� ...

, founded in 1761.

The educational system, headed by Harvard College, was the best in the 13 colonies. Newspapers

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide variety of fields such as politics, business, sports ...

became a major communications system in the 18th century, with Boston taking a leading role in the British colonies. Teenaged Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

(born on January 17, 1706, in Milk Street) worked on one of the earliest newspapers, The New-England Courant

''The New-England Courant'' (also spelled ''New England Courant''), one of the first American newspapers, was founded in Boston in 1721, by James Franklin. It was a weekly newspaper and the third to appear in Boston. Unlike other newspapers, i ...

(owned by his brother) until he ran away to Philadelphia in 1723. Five Boston newspapers presented a full range of opinions during the coming of the American revolution. In Worcester, printer Isaiah Thomas made the ''Massachusetts Spy

''The Massachusetts Spy'', later subtitled the '' Worcester Gazette'', (est.1770) was a newspaper published by Isaiah Thomas in Boston and in Worcester, Massachusetts, in the 18th century.

It was a heavily political weekly paper that was constan ...

'' the influential voice of the western settlers.

Farming was the largest economic activity. Most farming towns were largely self-sufficient, with families trading with each other for items they did not produce themselves; the surplus was sold to cities. and Fishing was important in coastal towns like Marblehead. Great quantities of cod were exported to the slave colonies in the West Indies. Merchant trade was based in Salem and Boston, and numerous wealthy merchants traded internationally. They typically stationed their sons and nephews as agents in ports around the empire. Their business grew dramatically after 1783 when they no longer were confined to the British Empire. Shipbuilding was a fast-growing industry. Most other manufactured products were imported from Britain (or smuggled in from the Netherlands).

Banking

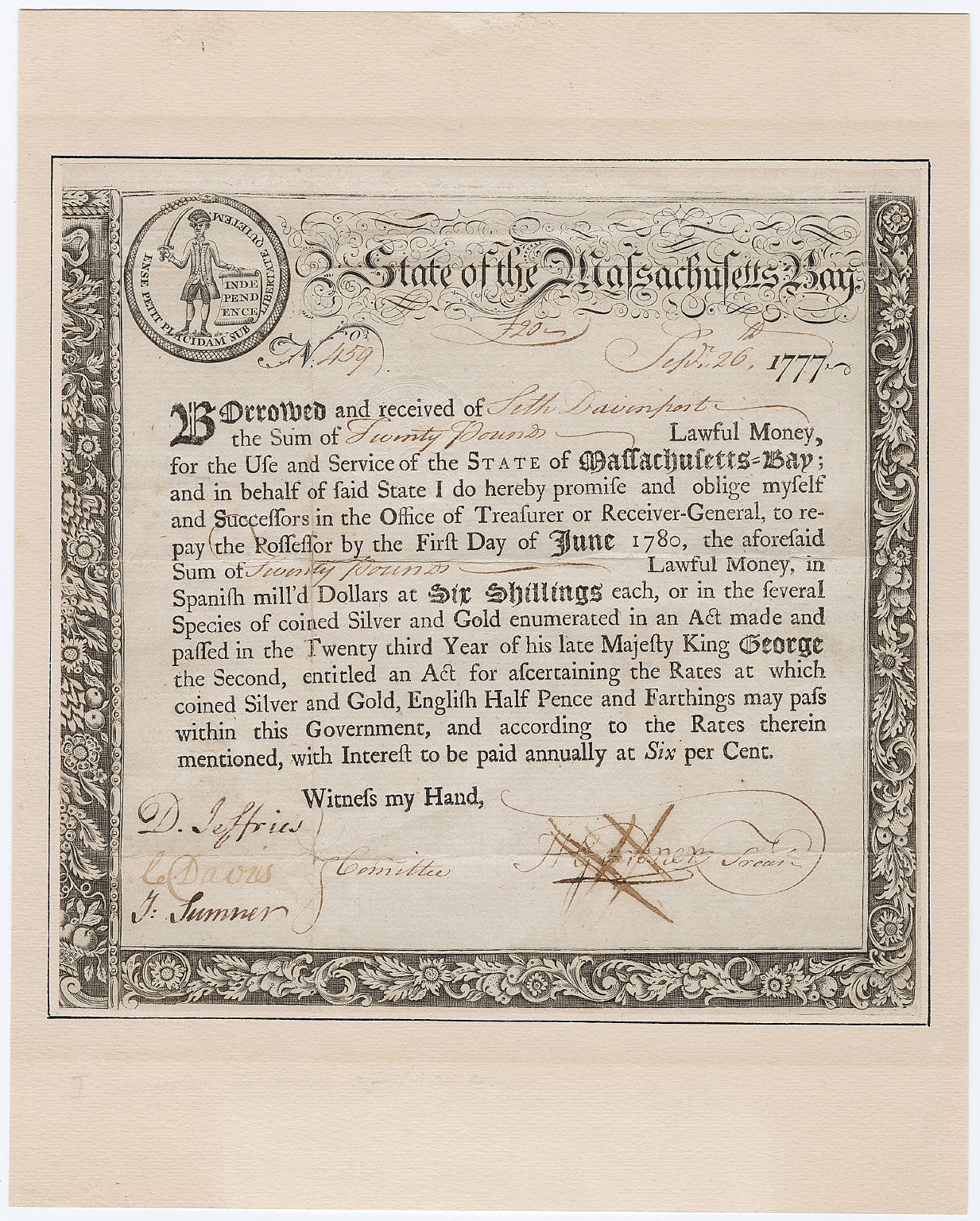

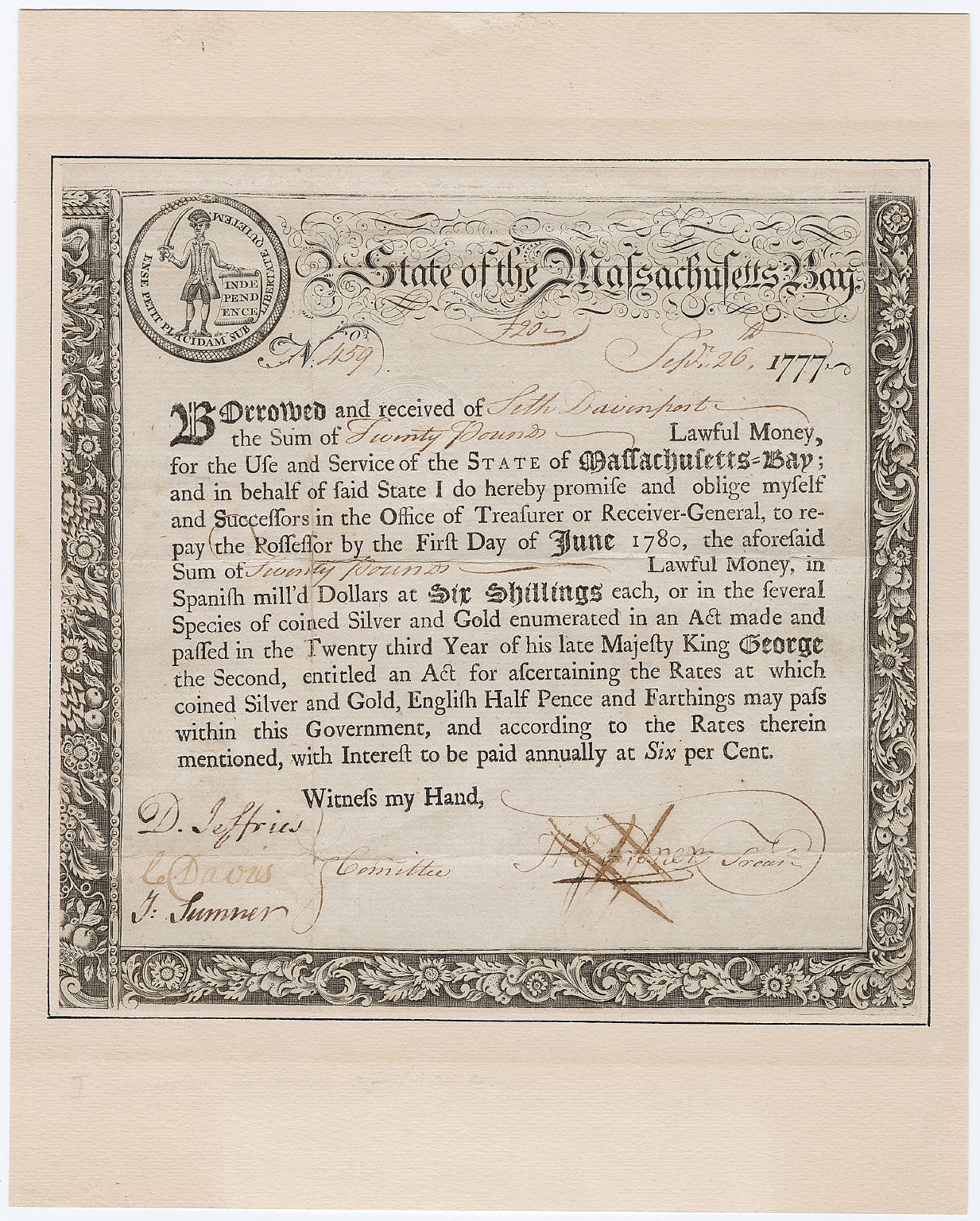

In 1690, the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

became the first to issue paper money in what would become the United States, but soon others began printing their own money as well. The demand for currency in the colonies was due to the scarcity of coins, which had been the primary means of trade.fiat

Fiat Automobiles S.p.A. (, , ; originally FIAT, it, Fabbrica Italiana Automobili di Torino, lit=Italian Automobiles Factory of Turin) is an Italian automobile manufacturer, formerly part of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, and since 2021 a subsidiary ...

paper currency. Under the 1751 act, the New England colonial governments could make paper money legal tender

Legal tender is a form of money that courts of law are required to recognize as satisfactory payment for any monetary debt. Each jurisdiction determines what is legal tender, but essentially it is anything which when offered ("tendered") in pa ...

for the payment of public debts (such as taxes), and could issue bills of credit as a tool of government finance, but barred the use of paper money as legal tender for private debts.[Larry Allen, "Currency Act of 1751 (England)" and "Currency Act of 1764 (England)" in ''The Encyclopedia of Money'', pp. 96-98.] Under continued pressure from the British merchant-creditors who disliked being paid in depreciated paper currency, the subsequent Currency Act of 1764

The Currency Act or Paper Bills of Credit Act is one of several Acts of the Parliament of Great Britain that regulated paper money issued by the colonies of British America. The Acts sought to protect British merchants and creditors from being pa ...

banned the issuance of bills of credit (paper money) throughout the colonies.

Wars with France

The colony fought alongside British regulars in a series of French and Indian Wars

The French and Indian Wars were a series of conflicts that occurred in North America between 1688 and 1763, some of which indirectly were related to the European dynastic wars. The title ''French and Indian War'' in the singular is used in the U ...

characterized by brutal border raids and attacks by Indians organized and supplied by New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spai ...

. Particularly in King William's War (1689–97) and Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

(1702–13), the colony's rural communities were directly exposed to French and Indian attacks, with Deerfield raided in 1704 and Haverhill raided in 1708. Boston responded, launching naval expeditions against Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and early ...

and Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

in both wars.

During Queen Anne's War, Massachusetts men were involved in the Conquest of Acadia (1710), which became the Province of Nova Scotia

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outsi ...

. The province was also involved in Dummer's War

Dummer's War (1722–1725) is also known as Father Rale's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the Wabanaki-New England War, or the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War. It was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the ...

, which drove Indian tribes from northern New England. In 1745, during King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in t ...

, Massachusetts provincial forces successfully besieged Fortress Louisbourg

The Fortress of Louisbourg (french: Forteresse de Louisbourg) is a National Historic Site and the location of a one-quarter partial reconstruction of an 18th-century French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Its two sie ...

. The fortress was returned to France at the end of the war, angering many colonists who viewed it as a threat to their security. During the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

, Governor William Shirley

William Shirley (2 December 1694 – 24 March 1771) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator who served as the governor of the British American colonies of Massachusetts Bay and the Bahamas. He is best known for his role in organi ...

was instrumental in the Expulsion of the Acadians

The Expulsion of the Acadians, also known as the Great Upheaval, the Great Expulsion, the Great Deportation, and the Deportation of the Acadians (french: Le Grand Dérangement or ), was the forced removal, by the British, of the Acadian pe ...

from Nova Scotia and trying to settle them in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. After the expulsion, Shirley also was involved in transporting New England Planters

The New England Planters were settlers from the New England colonies who responded to invitations by the lieutenant governor (and subsequently governor) of Nova Scotia, Charles Lawrence, to settle lands left vacant by the Bay of Fundy Campaign ( ...

to settle Nova Scotia on the former Acadian farms. Many troops from Massachusetts participated in the successful Siege of Havana

The siege of Havana was a successful British siege against Spanish-ruled Havana that lasted from March to August 1762, as part of the Seven Years' War. After Spain abandoned its former policy of neutrality by signing the family compact with Fr ...

in 1762. Britain's victory in the war led to its acquisition of New France, removing the immediate northern threat to Massachusetts that the French had posed.

Disasters

Boston was hit by a major smallpox epidemic in 1721. Some colonial leaders called for use of the new technique of inoculation, whereby a patient would get a weak form of the disease and become permanently immune. Puritan minister Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a New England Puritan clergyman and a prolific writer. Educated at Harvard College, in 1685 he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meeting H ...

and physician Zabdiel Boylston

Zabdiel Boylston, FRS (March 9, 1679 – March 1, 1766) was a physician in the Boston area. As the first medical school in North America was not founded until 1765, Boylston apprenticed with his father, an English-born surgeon named Thomas Boyls ...

led the drive for inoculation, while physician William Douglass and newspaper editor James Franklin led the opposition.

In 1755, about 4:15 am on Tuesday, November 18, was the most destructive earthquake yet known in New England. The first pulsations of the ground were followed for about a minute of tremulous motion. Next came a quick vibration and several jerks much worse than the first. Houses rocked and cracked; furniture fell over. Dr. Edward A. Holyoke, of Salem, wrote in his diary that he "thought of nothing less than being buried instantly in the ruins of the house." The shaking continued for two to three minutes more, and seemed to move from northwest to southeast. The ocean along the coast was affected; ships shook so much that sleeping sailors awoke, thinking they had run aground. In Boston, the earthquake threw dishes on the floor, stopped clocks, and bent vane-rods on churches and Faneuil Hall

Faneuil Hall ( or ; previously ) is a marketplace and meeting hall located near the waterfront and today's Government Center, in Boston, Massachusetts. Opened in 1742, it was the site of several speeches by Samuel Adams, James Otis, and others ...

. Stone walls collapsed. New springs appeared, and old springs dried up. Subterranean streams changed their courses, emptying many wells. The worst damage was to chimneys. In Boston alone, about a hundred were leveled; about fifteen hundred were damaged, the streets in some places almost covered with fallen bricks. Falling chimneys broke some roofs. Many wooden buildings in Boston were thrown down, and some brick buildings suffered; the gable ends of twelve or fifteen were knocked down to the eaves. Despite the danger and many narrow escapes, no one was killed or seriously injured. Aftershocks continued for four days.

Politics

The relationship between the provincial government and the crown-appointed governor was often difficult and contentious. The governors sought to assert the royal prerogatives granted in the provincial charter, and the provincial government sought to strip or minimize the governor's power. For example, each governor was ordered to enact legislation for providing permanent salaries for crown officials, but the legislature refused to do so, using its ability to grant stipends annually as a means of control over the governor. The province's periodic issuance of paper currency was also a persistent source of friction between factions in the province, due to its inflationary effects. Notable royal governors during this period were Joseph Dudley

Joseph Dudley (September 23, 1647 – April 2, 1720) was a colonial administrator, a native of Roxbury in Massachusetts Bay Colony, and the son of one of its founders. He had a leading role in the administration of the Dominion of New England ...

, Thomas Hutchinson, Jonathan Belcher

Jonathan Belcher (8 January 1681/8231 August 1757) was a merchant, politician, and slave trader from colonial Massachusetts who served as both governor of Massachusetts Bay and governor of New Hampshire from 1730 to 1741 and governor of New J ...

, Francis Bernard, and General Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of the ...

. Gage was the last British governor of Massachusetts, and his effective rule extended to little more than Boston.

Revolutionary Massachusetts: 1760s–1780s

Massachusetts was a center of the movement for independence from

Massachusetts was a center of the movement for independence from Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

, earning it the nickname, the "Cradle of Liberty". Colonists here had long had uneasy relations with the British monarchy, including open rebellion under the Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was an administrative union of English colonies covering New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies (except for Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvania). Its political structure represe ...

in the 1680s.[Goldfield, et al., p. 66.] The Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell tea ...

is an example of the protest spirit in the early 1770s, while the Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre (known in Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain as the Incident on King Street) was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which a group of nine British soldiers shot five people out of a crowd of three or four hu ...

escalated the conflict. Anti-British activity by men like Sam Adams

Samuel Adams ( – October 2, 1803) was an American statesman, political philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, and ...

and John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of the ...

, followed by reprisals by the British government, were a primary reason for the unity of the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

and the outbreak of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

. The Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord ...

initiated the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

and were fought in the Massachusetts towns of Lexington and Concord

Concord may refer to:

Meaning "agreement"

* Pact or treaty, frequently between nations (indicating a condition of harmony)

* Harmony, in music

* Agreement (linguistics), a change in the form of a word depending on grammatical features of other ...

. Future President George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

took over what would become the Continental Army after the battle. His first victory was the Siege of Boston

The siege of Boston (April 19, 1775 – March 17, 1776) was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War. New England militiamen prevented the movement by land of the British Army, which was garrisoned in what was then the peninsular town ...

in the winter of 1775–76, after which the British were forced to evacuate the city. The event is still celebrated in Suffolk County as Evacuation Day. In 1777, George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

and Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806), a Founding Father of the United States, was a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, serving as chief of artillery in most of Washington's campaigns. Following the ...

founded the Arsenal at Springfield, which catalyzed many innovations in Massachusetts' Connecticut River Valley.

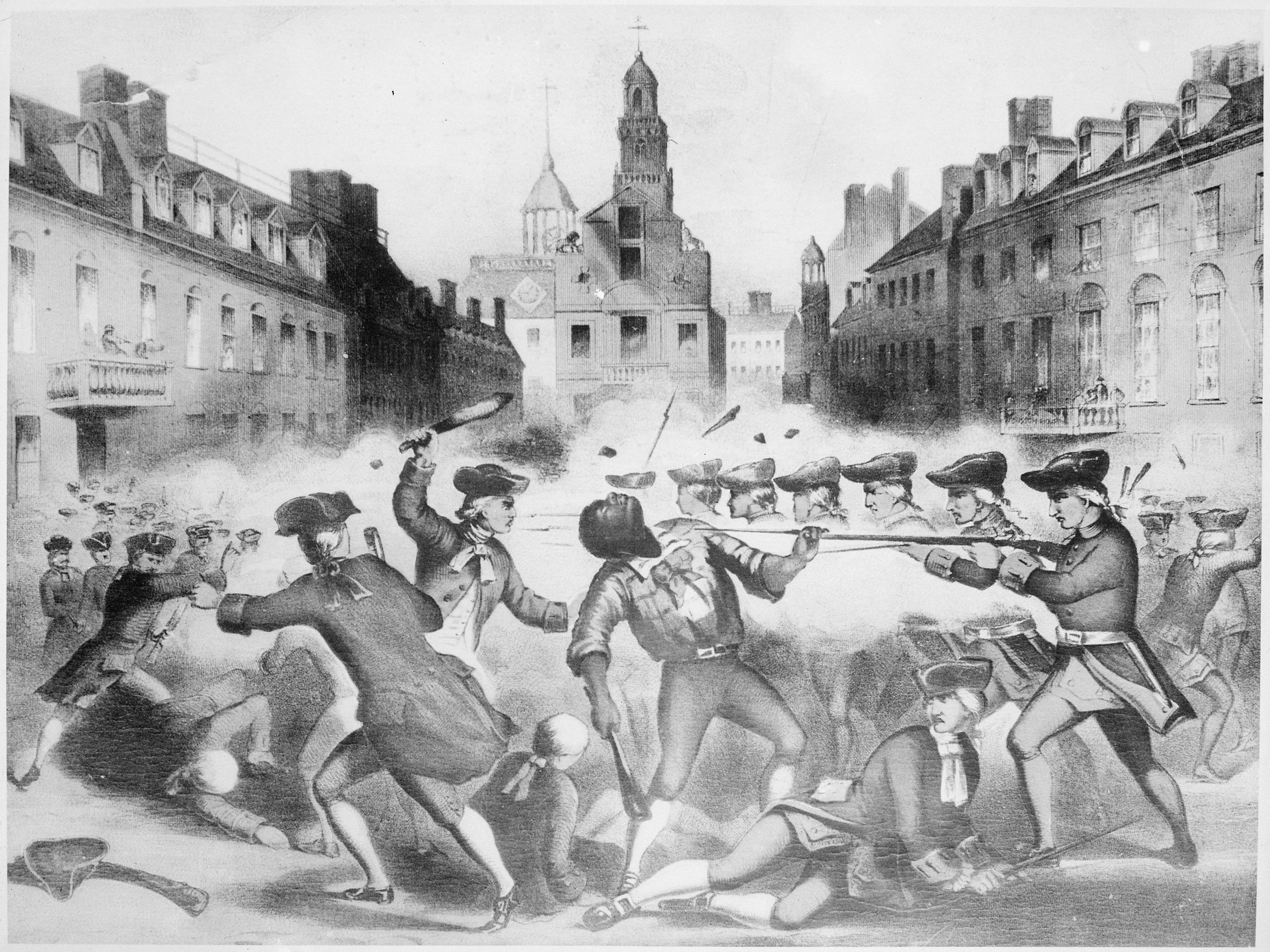

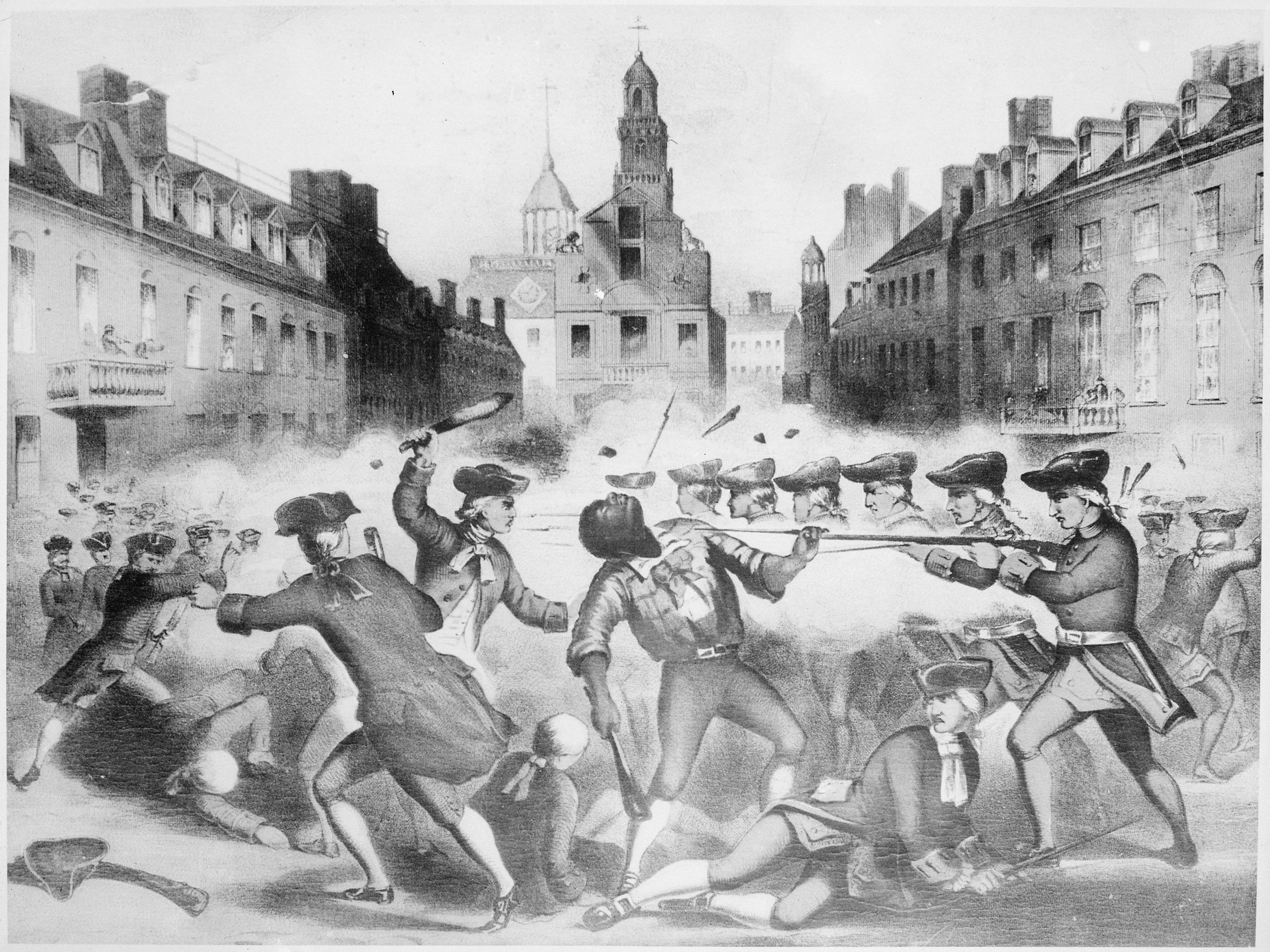

Boston Massacre

Boston was the center of revolutionary activity in the decade before 1775, with Massachusetts natives

Boston was the center of revolutionary activity in the decade before 1775, with Massachusetts natives Samuel Adams

Samuel Adams ( – October 2, 1803) was an American statesman, political philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, and ...

, John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

, and John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of the ...

as leaders who would become important in the revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

. Boston had been under military occupation since 1768. When customs officials were attacked by mobs, two regiments of British regulars arrived. They had been housed in the city with increasing public outrage.

In Boston on March 5, 1770, what began as a rock-throwing incident against a few British soldiers ended in the shooting of five men by British soldiers in what became known as the Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre (known in Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain as the Incident on King Street) was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which a group of nine British soldiers shot five people out of a crowd of three or four hu ...

. The incident caused further anger against British authority in the commonwealth over taxes and the presence of the British soldiers.

Boston Tea Party

One of the many taxes protested by the colonists was a tax on tea, imposed when Parliament passed the

One of the many taxes protested by the colonists was a tax on tea, imposed when Parliament passed the Townshend Acts

The Townshend Acts () or Townshend Duties, were a series of British acts of Parliament passed during 1767 and 1768 introducing a series of taxes and regulations to fund administration of the British colonies in America. They are named after the ...

, and retained when most of the provisions of those acts were repealed. With the passage of the Tea Act

The Tea Act 1773 (13 Geo 3 c 44) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. The principal objective was to reduce the massive amount of tea held by the financially troubled British East India Company in its London warehouses and to help th ...

in 1773, tea sold by the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

would become less expensive than smuggled tea, and there would be reduced profit-making opportunities for Massachusetts merchants traded in tea. This led to protests against the delivery of the company's tea to Boston. On December 16, 1773, when a tea ship of the East India Company was planning to land taxed tea in Boston, a group of local men known as the Sons of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty was a loosely organized, clandestine, sometimes violent, political organization active in the Thirteen American Colonies founded to advance the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. It pl ...

sneaked onto the boat the night before it was to be unloaded and dumped all the tea into the harbor, an act known as the Boston Tea Party.

American Revolution

The Boston Tea Party prompted the British government to pass the Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measure ...

in 1774 that brought stiff punishment on Massachusetts. They closed the port of Boston, the economic lifeblood of the Commonwealth, and reduced self-government. Local self-government was ended and the colony put under military rule. The Patriots formed the Massachusetts Provincial Congress

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress (1774–1780) was a provisional government created in the Province of Massachusetts Bay early in the American Revolution. Based on the terms of the colonial charter, it exercised ''de facto'' control over the ...

after the provincial legislature was disbanded by Governor Gage. The suffering of Boston and the tyranny of its rule caused great sympathy and stirred resentment throughout the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

. On February 9, 1775, the British Parliament declared Massachusetts to be in rebellion, and sent additional troops to restore order to the colony. With the local population largely opposing British authority, troops moved from Boston on April 18, 1775, to destroy the military supplies of local resisters in Concord

Concord may refer to:

Meaning "agreement"

* Pact or treaty, frequently between nations (indicating a condition of harmony)

* Harmony, in music

* Agreement (linguistics), a change in the form of a word depending on grammatical features of other ...

. Paul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, engraver, early industrialist, Sons of Liberty member, and Patriot and Founding Father. He is best known for his midnight ride to ale ...

made his famous ride to warn the locals in response to this march. On the 19th, in the Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord ...

, where the famous "shot heard 'round the world

"The Shot Heard 'Round the World" is a phrase that refers to the opening shot of the battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, which began the American Revolutionary War and led to the creation of the United States of America. It was an ...

" was fired, British troops, after running over the Lexington militia, were forced back into the city by local resistors. The city was quickly brought under siege. Fighting broke out again in June when the British took the Charlestown Peninsula in the Battle of Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill was fought on June 17, 1775, during the Siege of Boston in the first stage of the American Revolutionary War. The battle is named after Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts, which was peripherally involved in ...

after the colonial militia fortified Breed's Hill. The British won the battle, but at a very large cost, and were unable to break the siege. The British made a desperate attempt by using biological weapons

A biological agent (also called bio-agent, biological threat agent, biological warfare agent, biological weapon, or bioweapon) is a bacterium, virus, protozoan, parasite, fungus, or toxin that can be used purposefully as a weapon in bioterrorism ...

against the Americans by sending infected civilians with smallpox behind American lines but this was soon contained by Continental General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

who launched a vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

program to ensure his troops and civilians were in good health after the damage biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. Bio ...

caused. Soon after the Battle of Bunker Hill, General George Washington took charge of the rebel army, and when he acquired heavy cannon in March 1776, the British were forced to leave, marking the first great colonial victory of the war. Ever since, "Evacuation Day" has been celebrated as a state holiday.

Massachusetts was not invaded again but in 1779 the disastrous

Massachusetts was not invaded again but in 1779 the disastrous Penobscot Expedition

The Penobscot Expedition was a 44-ship American naval armada during the Revolutionary War assembled by the Provincial Congress of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The flotilla of 19 warships and 25 support vessels sailed from Boston on July 1 ...

took place in the District of Maine

The District of Maine was the governmental designation for what is now the U.S. state of Maine from October 25, 1780 to March 15, 1820, when it was admitted to the Union as the 23rd state. The district was a part of the Commonwealth of Massachuse ...

, then part of the Commonwealth. Trapped by the British fleet, the American sailors sank the ships of the Massachusetts state navy before it could be captured by the British. In May 1778, the section of Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and p ...

that later became Fall River

Fall River is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. The City of Fall River's population was 94,000 at the 2020 United States Census, making it the tenth-largest city in the state.

Located along the eastern shore of Mount H ...

was raided by the British, and in September 1778, the communities of Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard, often simply called the Vineyard, is an island in the Northeastern United States, located south of Cape Cod in Dukes County, Massachusetts, known for being a popular, affluent summer colony. Martha's Vineyard includes the s ...

and New Bedford

New Bedford (Massachusett: ) is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast region. Up through the 17th century, the area was the territory of the Wampanoag Native American pe ...

were also subjected to a British raid.

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

was a leader in the independence movement and he helped secure a unanimous vote for independence and on July 4, 1776, the United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

was adopted in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

. It was signed first by Massachusetts resident John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of the ...

, president of the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

. Soon afterward the Declaration of Independence was read to the people of Boston from the balcony of the State House. Massachusetts was no longer a colony; it was a state and part of a new nation, the United States of America.

Federalist Era: 1780–1815

A Constitutional Convention drew up a state constitution, which was drafted primarily by John Adams, and ratified by the people on June 15, 1780. Adams, along with Samuel Adams and

A Constitutional Convention drew up a state constitution, which was drafted primarily by John Adams, and ratified by the people on June 15, 1780. Adams, along with Samuel Adams and James Bowdoin

James Bowdoin II (; August 7, 1726 – November 6, 1790) was an American political and intellectual leader from Boston, Massachusetts, during the American Revolution and the following decade. He initially gained fame and influence as a wealthy ...

, wrote in the ''Preamble to the Constitution of the Commonwealth'':

Bostonian John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

, known as the "Atlas of Independence", was an important figure in both the struggle for independence as well as the formation of the new United States.Massachusetts Constitution

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the fundamental governing document of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, one of the 50 individual state governments that make up the United States of America. As a member of the Massachuset ...

in 1780 (which, in the Elizabeth Freeman

Elizabeth Freeman ( 1744 December 28, 1829), also known as Bet, Mum Bett, or MumBet, was the first enslaved African American to file and win a freedom suit in Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruling, in Freeman's favor, ...

and Quock Walker

Quock Walker, also known as Kwaku or Quork Walker (1753 – ?), was an American slavery, slave who sued for and won his freedom in June 1781 in a case citing language in the new Massachusetts Constitution (1780) that declared all men to be born fr ...

cases, effectively made Massachusetts the first state to have a constitution that declared universal rights and, as interpreted by Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice William Cushing

William Cushing (March 1, 1732 – September 13, 1810) was one of the original five associate justices of the United States Supreme Court; confirmed by the United States Senate on September 26, 1789, he served until his death. His Supreme Court ...

, abolished slavery).John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

, would go on to become the sixth US President.

The new constitution

Massachusetts was the first state in the United States to abolish slavery. (Vermont, which became part of the U.S. in 1791, abolished adult slavery somewhat earlier than Massachusetts, in 1777.) The new constitution also dropped any religious tests for political office, though local tax money had to be paid to support local churches. People who belonged to non-Congregational churches paid their tax money to their own church, and the churchless paid to the Congregationalists. Baptist leader Isaac Backus

Isaac Backus (January 9, 1724November 20, 1806) was a leading Baptist minister during the era of the American Revolution who campaigned against state-established churches in New England. Little is known of his childhood. In "An account of the lif ...

vigorously fought these provisions, arguing people should have freedom of choice regarding financial support of religion. Adams drafted most of the document and despite numerous amendments it still follows his line of thought. He distrusted utopians and pure democracy, and put his faith in a system of checks and balances; he admired the principles of the unwritten British Constitution. He insisted on a bicameral legislature which would represent both the gentlemen and the common citizen. Above all he insisted on a government by laws, not men. The constitution also changed the name of the Massachusetts Bay State to the . Still in force, it is the oldest constitution in current use in the world.

Shays' Rebellion

The economy of rural Massachusetts suffered an economic depression after the war ended. Merchants, pressured for hard currency by overseas partners, made similar demands on local debtors, and the state raised taxes in order to pay off its own war debts. Efforts to collect both public and private debts from cash-poor farmers led to protests that flared into